Greetings All,

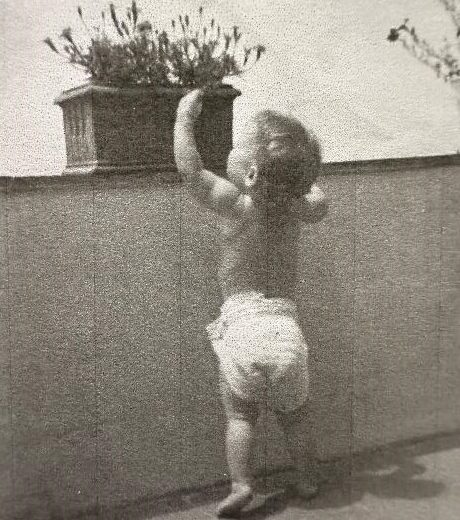

Here we are, on the brink of springtime. The vernal equinox on March 21st is one of only two times in the year when the Earth’s axis is tilted neither toward nor away from the sun, resulting in an equal amount of night and day. With the lengthening light and reawakening of nature, I hope this moment offers you a sense of possibility and pleasurable anticipation. I can almost remember being in that state in the photo above, always being drawn to flowers and perhaps lavender most of all, my lifelong “power herb.”

Each year, the arrival of spring reminds me of a favorite childhood classic, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1910 The Secret Garden. In it, sulky, sickly orphan Mary Lennox is sent from India to live in a vast, dreary estate in Yorkshire as the ward of her grief stricken, widowed uncle. Wandering alone through the grand, deserted gardens, she begins to connect with the natural world, eventually finding her way into a mysterious walled garden that has been locked and neglected since her aunt’s untimely death there years before. Along the way, she encounters Dickon, a rosy-cheeked young animal whisperer of the moors; her hidden-away, invalid cousin Colin; and a lively European robin who shows her the key to the secret garden, buried in the dirt. Nourished by the magic of nature, discovery, and friendship, Mary and the other children bring the garden back to life as spring exquisitely unfolds.

As an adult, now I can see the colonialism, racism, and classism that pervade The Secret Garden, being as it is a product of its time and the author’s conditioning. This is a challenge when engaging with any compelling work of art reflecting distasteful beliefs, not just from other eras, but our own. A case could be made for the ways The Secret Garden, written in the waning years of the British empire, deconstructs these through the death by cholera of Mary’s parents and the decimation of their privileged imperialist life, as well as through the growth of deep, transformative friendship across class lines between the children who gather in the secret garden.

I’ll stop short of suggesting that Frances Hodgson Burnett baked a critique of imperialist decadence into The Secret Garden, although her biography has interesting elements of movement between marginal family prosperity and gentility and outright hardship—adversity that, like that other treasured nineteenth-century female author of children’s books, Lousia May Alcott, was part of what led her to write, and seek paid publication, for her work. Marriage and her success as a writer increased her fortunes. By the 1890’s, Burnett was able to lease Great Maytham Hall, a showy eighteenth-century manor house with extensive gardens in Kent, which casts her more as the kind of nouveau riche, wannabe gentry characteristic of the Gilded Age.

Against this complicated backdrop, I still continue to be moved by The Secret Garden’s poignant springtime themes of awakening, connection, and the healing power of nature. The suspenseful incipience that is a defining quality of this time of year, with springtime emerging but not yet fully manifested, gains momentum across the course of the narrative.

“She thought she saw something sticking out of the black earth—some sharp little pale green points. “They are tiny growing things and they might be crocuses or snowdrops or daffodils,” she whispered. She bent very close to them and sniffed the fresh scent of the damp earth.”

This is potential presenting itself, and the interplay between our familiarity with the process of spring’s unfolding and the fresh wonder and upwellings of hope it can still inspire, year after year. On recent visit to Filoli Historic House and Gardens (the Bay Area’s version of a fancy manor house), some of the earliest daffodil and narcissus varieties were in full flower, but it was these budding clumps of later-blooming “Minnow” daffodils (below) that caught my attention. It’s human nature to want to see things at their most glorious apex, though doing so also carries with it the foreshadowing of loss: it’s only downhill from here. Savoring incipience (from the Latin incipere, to begin) is like inhabiting the pause in breathing between the top of an inhalation and the release of exhalation, or like channeling the attitude of Zen shoshin, or “beginner’s mind,” whose openness, eagerness, and lack of preconception call, paradoxically, upon the sustained cultivation of wisdom.

Slowing down around this moment of natural incipience is beautiful way to honor what’s here at this time of year. This could include considering what developments you might be on the verge of; how to best cultivate what you want to see flourish; leaning into the experience of being on the threshold of one season and another, or one phase of life, and another; and spending plenty of time outdoors and/or with plants, whether gardening or in nature, tuning into the wonderful unfoldings of the season.

In terms of my own momentum, having just taught the latest chapter (Winter) in my Four Seasons of Mindfulness series, I’m feeling drawn to create room to pause in the space of potential rather than plunging immediately into the next project. This will involve inviting fresh energy and insights through travel over the next few weeks. Upon my return, I’ll have spring cleaning and decluttering, both literal and spiritual, on my radar; consolidating previous mindfulness teachings to share in new forms; continuing to practice clinically; and developing a “Mindfulness 101” class for our folks at Gateway.

I’ll be in touch with information about new offerings and upcoming events, and meanwhile send warm and hopeful wishes for springtime to bring you many gifts of joy, wonder, and possibility.

Andrea